By Vikas Datta

Call it fate but literature sometimes sees translations or adaptions becoming much more famous than the original work. Like this mid-Victorian era translation of some Persian poetry which became part of the English literary tradition, besides influencing the likes of Agatha Christie, Daphne du Maurier, O. Henry, Eugene O’Neill, Nevil Shute, Jorge Luis Borges, Harivansh Rai Bachchan and Paramhansa Yogananda, not to mention turning up in a Hollywood Western (Gregory Peck-starrer “Duel in the Sun”) and a Bollywood song. What’s more, Edward FitzGerald’s translation of Omar Khayyam’s “Rubaiyat” also ended up re-introducing the poet’s work to his native land.

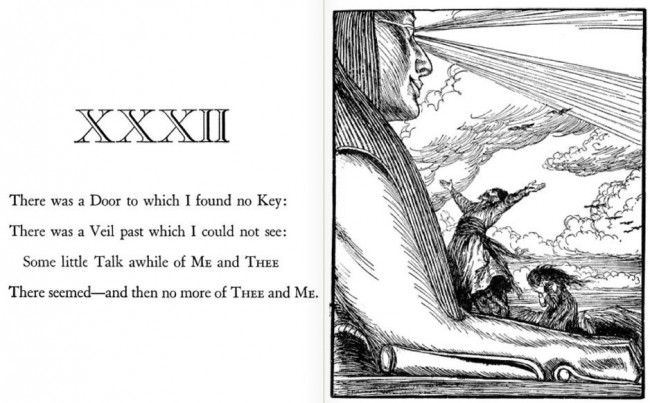

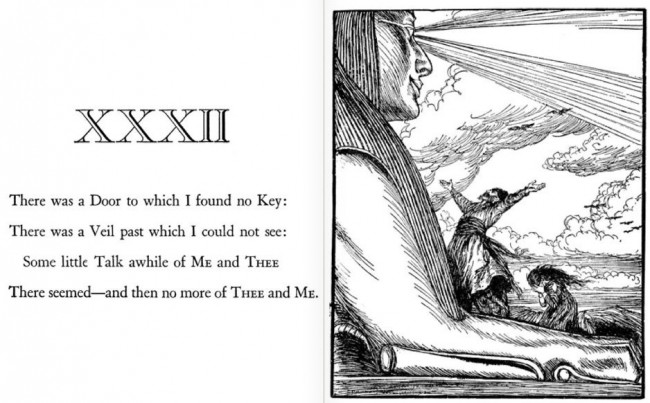

FitzGerald (1809-83), who counted William Thackeray and Alfred Tennyson as friends, was inspired to translate Khayyam after his Oxford Persian professor E.B. Cowell discovered a manuscript in the Asiatic Society’s Calcutta (now Kolkata) library in 1857. He published his first translation, with 75 quatrains, anonymously in 1859, but it did not create much of a stir until 1861, when poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti discovered and popularised it. There were five editions, the second (1868) with 110 quatrains, but the third (1872), fourth, (1879) and fifth (1889, posthumous) stuck to 101. The first, second, and fifth differ significantly, while the second and third are almost identical, as are the last two.

The first and the fifth are the most referenced though a difference is discernible: “Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough/A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse – and Thou/Beside me singing in the Wilderness -/And Wilderness is Paradise enow” of the first in the fifth is “A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,/A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread–and Thou/Beside me singing in the Wilderness–/Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!”.

FitzGerald has been criticised for not maintaining fidelity to the original’s letter and spirit but himself admitted he did not do a translation but a “transmogrification”. In a letter to Cowell in 1858, he termed his work “very un-literal as it is. Many quatrains are mashed together: and something lost, I doubt, of Omar’s simplicity, which is so much a virtue in him”.

But his work’s sonorous, evocative phrases persist, and like the Bible and Shakespeare’s plays, have inspired many titles like Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novel “Some Buried Caesar”, O’Neill’s play “Ah, Wilderness!”, Christie and Stephen King’s stories “The Moving Finger”, Daphne du Maurier’s memoir “Myself when Young” and Shute’s “The Chequer Board”.

They gave Hector Hugh Munro his pen-name “Saki”, while O. Henry’s story “The Handbook of Hymen” refers to a book by “Homer KM” with the character “Ruby Ott” and another story is “The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball.” Borges, whose father translated FitzGerald into Spanish, discusses it in “The Enigma of Edward FitzGerald” and refers to it in various poems.

Closer to home, poets Maithili Sharan Gupta and Harivanshrai Bachchan translated it into Hindi while it inspired the latter’s own “Madhushala”. It was translated into various Indian languages (Bengali by Kazi Nazrul Islam), while Yogananda provided an interpretation in “Wine of the Mystic”.

Iranian author Sadeq Hedayat, who made the first modern study of the Rubaiyat in Persian, held that FitzGerald’s version re-evoked interest in Khayyám’s poetic legacy in his homeland, where he had been honoured as the greatest of mathematicians and astronomers, but never among the great poets.

The work also inspired a range of clever parodies – whether by Kipling whose “Rupaiyat of Omar Kalvin” is British India’s then financial administrator lamenting lack of funds, or a band of funny, innovative Americans like J.L. Duff’s lament on Prohibition in “The Rubaiyat of Ohow Dryyam”: “Wail! For the Law has scattered into flight/Those Drinks that were our sometime dear delight;/And still the Morals-tinkers plot and plan/New, sterner, stricter Statues to indite”; Oliver Hereford’s Persian cat version: “They say the Lion and the Lizard Keep/The Courts where Jamshyd gloried and drank deep/The Lion is my cousin; I don’t know/Who Jamshyd is-nor shall it break my sleep”, or Caroyn Welles’ “The Rubaiyat of Bridge”.

“The Rubaiyyat of Omar Cayenne” is Gelett Burgess’ peppery attack on publishers and critics: “Important Writers bound to feed ITS taste/For Literature and Poetry debased;/Hither and thither pandering we strive,/And one by one our Talents are disgraced”, and the misogynistic, nicotine lover in Wallace Irwin’s “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Jr.”: “Come, fill the Pipe, and in the Fire of Spring/The Cuban Leaves upon the Embers fling,/That in its Incense I may sermonize/On Woman’s Ways and all that sort of Thing.”

And then about FitzGerald himself in his style: “Myself now old am still the Suffolk-born/Have been to London once or twice but scorn/To venture where the Sufis weave their Spells/And Minarets the cloudless skies adorn”. Or take “A joint of Lamb, a Pint of Beer, and Thou/Khayyam of Naishapur, I will allow/To pay for them, but for the Rest/Woodbridge to me is Wilderness enow” or even “Let old Fitzgerald your Example be/Who spends his Life in Suffolk by the Sea/In Khorasan, may Sultan Mahmoud reign;/I have invited Tennyson for tea.”

It’s hard to find any other poetry that gripped and exercised the imagination more!