BY JYOTHSNA HEGDE

The title “These Americans,” by Jyotsna Sreenivasan initially had me thinking that it chronicled a first-gen immigrant perspective of the adopted country and culture. It did and sprawled surprisingly beyond. Sreenivasan’s penchant for keen observations and her organic approach to storytelling is an all-encompassing, heartwarming collection of narratives of “These Americans,” along with the second-generation immigrant kids who identify themselves as more American than they do Indian.

While the characteries and circumstances of each of the eight stories and a novella are varied, Sreenivasan’s attention to detail shines through in her placement of each of her stories, which are built within a life-cycle framework, each story representative of a certain stage in life beginning with birth and ending with death. Opening with a narrative about giving birth in the US, progressing to the formative years in the next, teenage rebellion, the burden of expectations, inter-cultural marriages, the inherent issues in these cross-cultural relations, the support and love an immigrant child internally longs for despite denouncing it outwardly, communication between parents and children, or lack of it thereof, old friendships that harbor hope and bring despair– Sreenivasan wraps up with a heart-wrenching novella involving the inevitable end– death.

“He is an American, who, leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds,” wrote Frenchman J.Hector St. John Crevecoeur in an article back in 1782, in answer to the question “What Is an American?” Definitions have changed since then. While Indian Americans, post 1965, have adhered to the new government, they have also transplanted their cultural and religious heritage, and have incorporated them into their distinct bicultural lifestyle. One of the ways the diaspora deals with both aspects is often by compartmentalizing the two forms. Acutely aware of and readily accepting of cultural differences, first-generation Indian Americans attempt to preserve Indian culture within the confines of their homes and adapt to the American way of life on the outside. While second-generation Indian Americans also compartmentalize, their conflicts typically arise from the cultural clash of American Individualism versus Indian communitarianism, particularly reflected in the career choices, which are most generally based on their impact on the family’s financial wellbeing and not the individual’s.

The strength in Sreenivasan’s writing is her ability to suffuse occasional, unexpected humor in her poignant portrayal of these immigrant conflicts within and between these generations, some of which drawn from her own experiences growing up as a second-generation immigrant, but, with plenty of room for reader’s reflections.

Mirror, mirrors the cultural conflict of a new immigrant mother, who barely began to comprehend the American way of life including understanding the difference between being smiled at and laughed at, is faced with the situation of having her first born delivered by a male obstetrician and then the option to “look at” the baby as she makes her entry to the world. “Here in America, they have things like that, so Amma can see her princess right away,” Prema tells the newborn.

In Home, recently remigrated Amiya faces the anguish of resetting to American mode and the inherent challenges, she encounters. While celebrating International Fair at school, Amiya is left wondering if there was really nothing Italian about her class’s table or Norwegian about Cheryl’s table, as she concludes, “Maybe the international fair was just—American.”

Revolution splashes unexpected humor even as it deals with the devastating effects of divorce on the kids. A third person narrative, the story zooms into the son of the family, Neel, who travels all the way to India with his dad with the only purpose of linking Gandhi to his family history, because, as Mr. Cartig had put it, “He’s perhaps the greatest leader since Jesus.” In Neel’s eventual discoveries and reflections, Sreenivasan highlights the complex impact of divorce on immigrant children and the insecurities it breeds.

Dreams features those variant families from the “Model Minority” title bestowed on the South Asian diaspora, who are outwardly every bit “model”, but in complete denial when their son strays off path. Despite plenty of evidence, Dr. Shastry, who actually goes to County’s Children’s Services for his once-a-week volunteer shift, refuses to acknowledge any counseling for his wayward son while Mrs. Shastry blissfully ignores the faint smell of cigarettes coming from the kids’ clothes wondering about these American schools, where they must allow the teachers to smoke. “What kind of example is that for the children?”

Drawing perhaps from her own experiences, quite a few stories focus on the mother-daughter dynamics. The Sweater underscores the lack of communication between a mother and her daughter, where the daughter assumes her mother has never been happy with her, and not just her knitting. “I was always careless. I’m too messy, too impatient, too disobedient,” she tells herself. The symbolic “hole” in the sweater, she eventually figures could perhaps be fixed, after all.

In Mrs Raghavendra’s Daughter, Sreenivasan traces a mother’s journey of acceptance of her daughter’s sexual orientation. A mother who once prayed to Vishnu, Lakshmi, and Ganesha to keep Anjana away from American boys, has to come to terms with the fact that perhaps her daughter is happy with Susan.

Relationships are never easy and initiating, developing and maintaining them

tends to be even more challenging, bearing its own set of issues when relations

are multicultural. The “Vase”, a gift by

visiting childhood friend, Liz, sets off Revathy on snapshots of memories that

attempt to reconnect, even as she discovers how little she really knew about

her best friend, and an apparent unhappiness that hovers over her in the

present. “I don’t want to take time away from my own life to support her that

much. I don’t love her enough for that. So I sent her a couple of books. She

doesn’t even like to read.” Liz, still a “skinny sixth grader with a blonde

mullet, lives in hope that she has ‘RAY-vuh-tee’ by her side.

“My dad always said, “These Americans love to take risks.” I resented his stereotype, muses an Indian American wife as the family decides to an impromptu outing on a bright and sunny Perfect Sunday, even as a looming financial crisis threatens to cast a dark shadow on the family. “I was more like my dad in the sense of being risk-averse,” she reflects, praying to Lord Ganesha, with closed eyes, accentuating the innate Indianness that thrives within, despite being born and raised in a foreign country.

Sreenivasan concludes with Hawk, a novella, which is a revised version of her earlier On the Brink of Bloom, also a finalist of the PEN/Bellwether Prize. This is another heart-rending tale that touches upon the trials and tribulations of a mother and daughter who struggle to find their bearings, in turmoil, with the mother worrying about neglecting her daughter when she was young and concealing a professional secret from family, while the daughter faces her failures personally and professionally, both estranged at home and discriminated at work. The Hawk, symbolizing a powerful bird, which can be potentially tamed but treasures his freedom, much like these women, and delves deep into the superficiality of diversity, conflicts of a talented physician is raising her only child, the rebellious child that ultimately wants to rise up to expectations, of aging, and choices made on a daily basis that define as people.

In her blog, Sreenivasan elaborates on the title, all too familiar in the diaspora circles, which originates from a phrase her immigrant parents often said to refer to non-immigrant Americans. Much like the phrase, Sreenivasan, who holds an MA in English literature from the University of Michigan, draws richly from her and other immigrant stereotypes, weaving these experiences insightfully and intrinsically in each of her narratives, and crafting a captivating and comfy quilt, the kind that gets passed down generations. And the subtle humor skillfully imbued amidst serious situations will always bring a smile, each time you encounter These Americans.

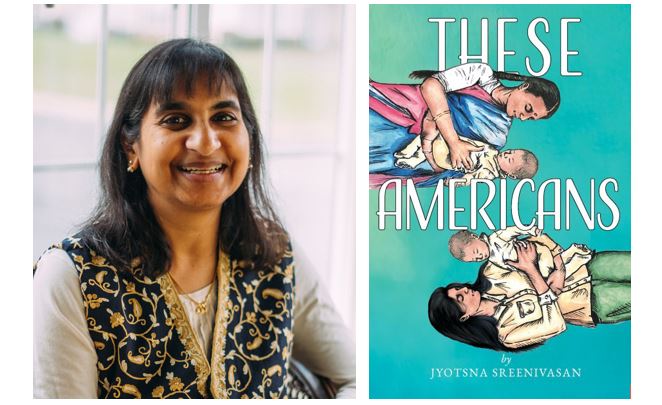

About the Author:Jyotsna Sreenivasan, the daughter of Indian immigrants, was born and raised in Ohio. She earned an M.A. in English literature from the University of Michigan. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous literary magazines, and she has received literature grants from the Washington, D.C., Commission on the Arts and Humanities. She currently lives and works in Columbus, Ohio. Website: https://secondgenstories.com/